Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929)

CLEMENCEAU’S LANDS

Clemenceau and the Vendée

Clemenceau in Paris

Clemenceau and the United States

Clemenceau the traveler

STATESMAN, POLITICAL FIGHTER

Early political years

The Panama scandal

The Dreyfus affair

Clemenceau, minister of the Interior

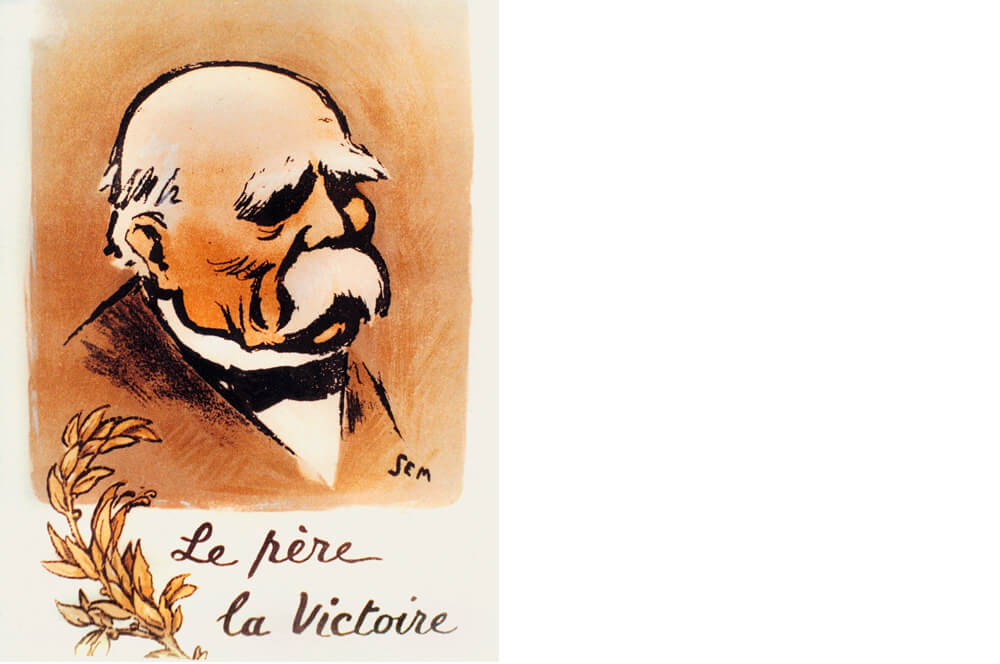

Le Père la Victoire

MAN OF LETTRERS – FRIEND TO ARTISTS

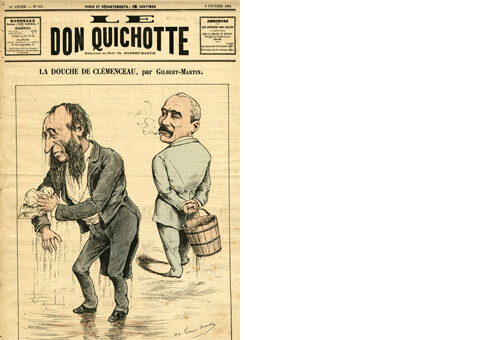

Clemenceau the journalist

Clemenceau and the artists

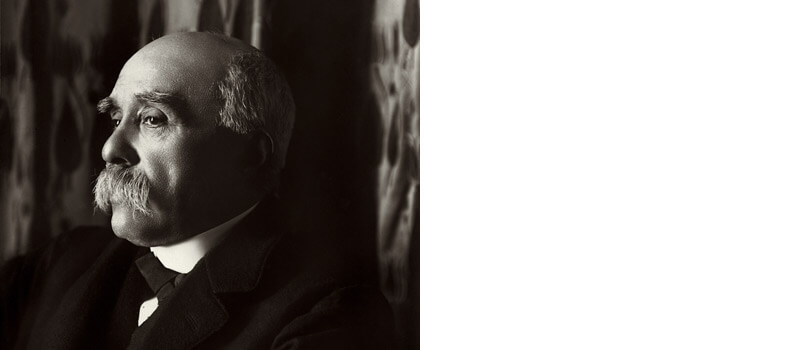

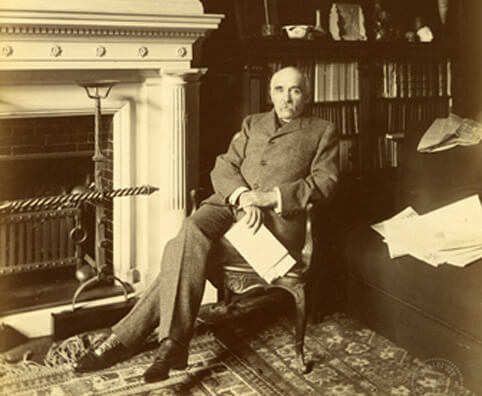

GEORGES CLEMENCEAU (1841-1929)

From his beginnings in Second Empire Vendée through his final years in interwar Paris, Georges Clemenceau dedicates his life to serving justice and beauty. He is a statesman, a literary figure and a lover of the arts.

His republican convictions are forged by opposition to Napoléon III. As a doctor turned deputy in 1876, he pushes for the amnesty of the Communards. Both in parliament and the press, he fights for equality, liberty and secularism and against intolerance and colonialism. Social issues are the heart of his battle. After losing his parliamentary seat in 1893, he becomes a fierce supporter of Dreyfus’s innocence from 1897 onwards and campaigns for an end to capital punishment. As a theater lover, writer and collector, he defends popular culture and is passionate about Asian art.

Head of government from 1906 to 1909, he is a demanding interior minister and a stubborn reformer. As a senator in 1914, he rails both at the front and through his pen against the incompetence of the civil and military authorities, before leading the nation to victory as President of the Council and Minister of War from November 1917. Alongside France’s allies, he then negotiates the Treaty of Versailles.

After retiring from politics, Clemenceau publishes his memoirs, promotes the works of Claude Monet and travels extensively.

A truly free and multitalented man, Clemenceau fights throughout his life for a strong and generous republic.

CLEMENCEAU’S LANDS

The Vendee is Clemenceau’s native region. Despite his attachment to « its fields, farms and footpaths », he moves first to Nantes and then Paris for medical studies, where as a young doctor he is attracted by politics. After an unhappy love affair, he leaves to discover America and its democracy. With the defeat of 1870 and the fall of the Empire, Clemenceau the MP enjoys visiting his friend Admiral Maxse in England or ‘taking the waters’ at Carlsbad in Austrian Bohemia. In Normandy, he owns a small château for a time in Bernouville. He travels to Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil on a lecture tour in 1910, while in the 1920s and now retired from politics, Clemenceau divides his time between Paris and his house in Bélébat in the Vendee. Egypt and Asia, whose civilizations fascinate him, are the destinations for two long voyages during these later years. In 1922, he makes a final and congenial visit to the United States.

Clemenceau and the Vendée

Georges Clemenceau is born on 28 September 1841 in Mouilleron-en-Pareds in the Vendee. His early years are spent with his parents, brothers and sisters in the Aubraie chateau near Sainte-Hermine. As a student in Nantes and Paris, he frequently travels home to Aubraie, continuing to visit until his father’s death in 1897. After 1869, he moves his young American wife to the chateau.

In 1920, Clemenceau rents a fisherman’s house on the shore at Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard, near Sables d’Olonne, known as Bélébat, which he nicknames the shack.

In Bélébat, he works on his final books and likes to host his family and close friends, such as Claude Monet in 1921.

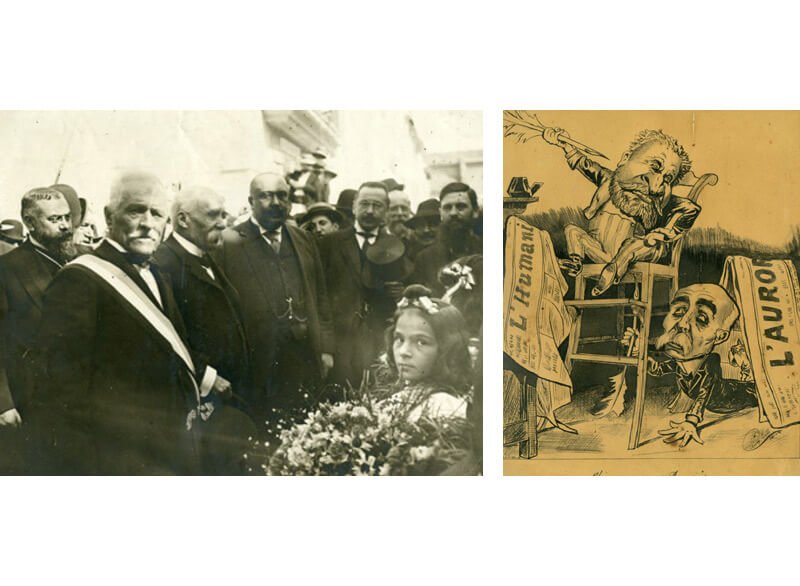

In 1922, Clemenceau, the Father of Victory, inaugurates a war memorial close to the Aubraie chateau that depicts him surrounded by WWI soldiers. His last will confirms his loyalty to the region: « I want to be buried next to my father at Colombier », which is near Mouchamps and only 20km from his native village. There is no tombstone, but a stele of Minerva by Francois Sicard keeps watch over the two graves.

Clemenceau in Paris

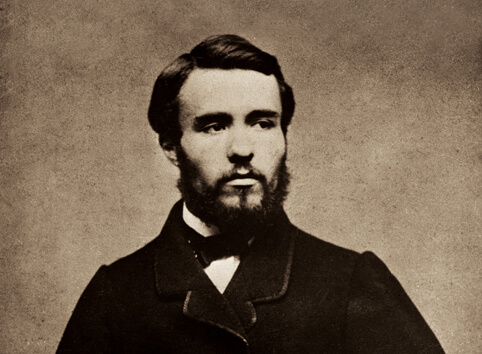

Clemenceau arrives in Paris in October 1861 at the age of twenty accompanied by his father Benjamin, who introduces him to republican circles and his friend Etienne Arago. He moves to the Latin Quarter, where he frequents the cafes and writes a series of political-literary reviews in short-lived journal, Le Travail that attack authors favorable to the government. In 1862, he is imprisoned for 77 days in Mazas prison for having called for protests during the anniversary of the proclamation of the Second Republic. At Mazas, Clemenceau meets political activist Auguste Blanqui, nicknamed « the imprisoned », and becomes a supporter. He defends his medical thesis inspired by positivist thought in 1865 under the direction of Charles Robin.

Clemenceau and the United States

Georges Clemenceau is a 24-year-old doctor when he moves to the United States in 1865. Remaining for four years, he teaches French, learns English and, like Toqueville before him, discovers American democracy. As foreign correspondent for le Temps, he is a witness to the country’s reconstruction following the Civil War. It was also there that Clemenceau meets Mary Plummer, his wife and the future mother of his children.

Much later, following his retirement from all political activity in January 1920, he publicly voices his concerns that the United States was surrendering to isolationist temptations after failing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles for which President Wilson had so greatly contributed. He returns to the United States without any official mandate in 1922, using a triumphal reception by the authorities and public to call on Americans- firmly, gracefully and as a friend- not to turn their back on the world and to continue serving peace.

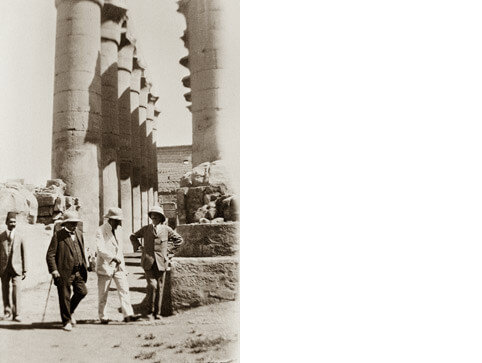

Clemenceau the traveler

« The French do not travel enough and live in ignorance of geography » complains Clemenceau, the globe trotter. Despite a chronic lack of money or time, he is able to satisfy his desire to visit other places. In the Americas, he travels the east coast of the United States, Canada, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil. In more familiar Europe, he likes to visit the United Kingdom, Greece, Belgium and Austria-Hungary.

In Africa, he travels in later years to Egypt and Djibouti. Asia is the destination for his last major voyage: Ceylon, British India, Burma, Singapore, the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago. Meeting other peoples, understanding their culture and admiring the beauty of their lands guide Clemenceau’s approach to travel.

STATESMAN, POLITICAL FIGHTER

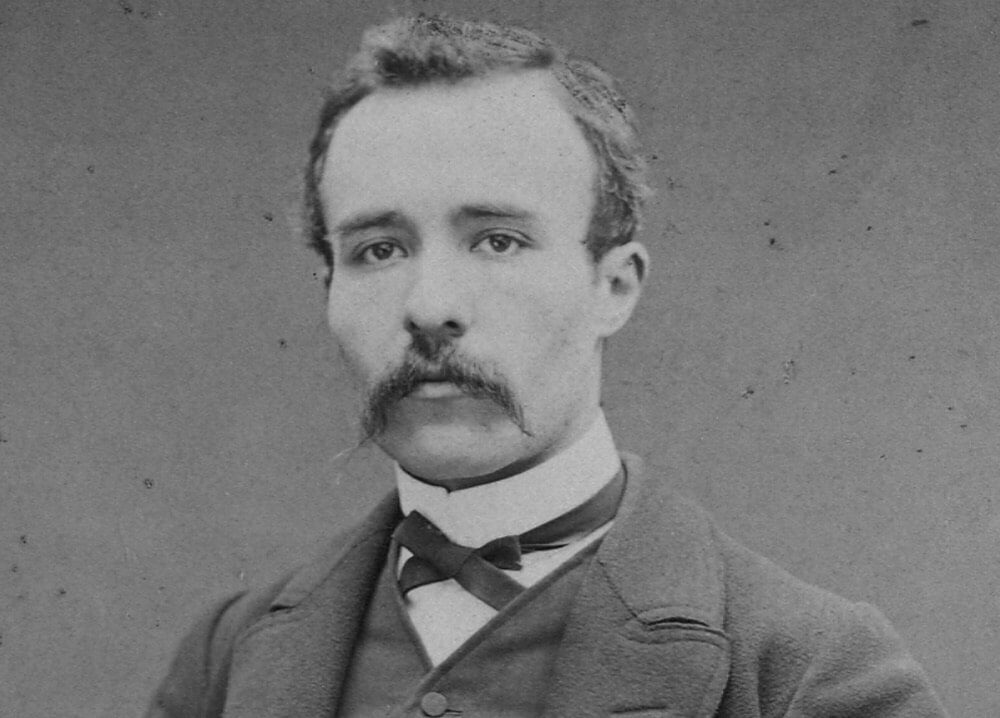

Georges Clemenceau’s long political career begins in republican opposition during the late Second Empire and concludes after the First World War. At each stage– the Paris siege of 1870, mayor of Montmartre at the start of the Commune, deputy for Paris and then the Var, the Panama scandal and exit from parliament, the journalist crusader unwavering in defense of Captain Dreyfus, senator for Var, interior minister, twice President of the Council– Clemenceau stands out as an unrivalled statesman. Loved and admired by some, hated and opposed by others, he never ceases during both peace and war, his often lonely struggle for the republic of his dreams. A man of constant action, he rebels continually against injustice and without compromise (and sometimes without subtlety).

Early political years

On 18 January 1871, King William I of Prussia is proclaimed Emperor of Germany at Versailles and armistice is signed with the German invader a week later. Georges Clemenceau, mayor of Montmartre and Paris deputy, refuses to accept the annexation of Alsace and Moselle and resigns from the National Assembly. In March 1871, he welcomes the patriotic uprising in Paris, without officially joining the Commune. Again elected deputy for Paris’s 18th district in 1876, Clemenceau breaks with Gambetta and the rest of the government shortly after the republican success in 1877, judging them too cautious in their approach to reform. He campaigns alongside Victor Hugo for amnesty for the Communards. Reelected as deputy on a radical program in 1881, he becomes opposition leader for the extreme left and fights for his vision of a strong and united republic for all citizens.

Actively opposed to colonialization, Clemenceau draws on his eloquence in parliament to bring down successive minsters, including Jules Ferry, his main adversary.

The Panama scandal

As the 1893 legislative elections approach, Clemenceau is the target of a violent campaign in parliament and the press concerning his close relationship with Cornélius Herz, a swindler implicated in the Panama scandal, who had helped finance his newspaper, La Justice. Clemenceau responds in a notable speech in his electoral district of Salernes, Var where he rejects the attacks and evokes the entirety of his public life and personal integrity. « Where are the millions? », he says. Nevertheless, he is beaten and would remain out of public office for 13 years, instead dedicating himself to making his living as a journalist. Short of funds, he auctions his collections during these years and moves to the modest apartment at rue Franklin.

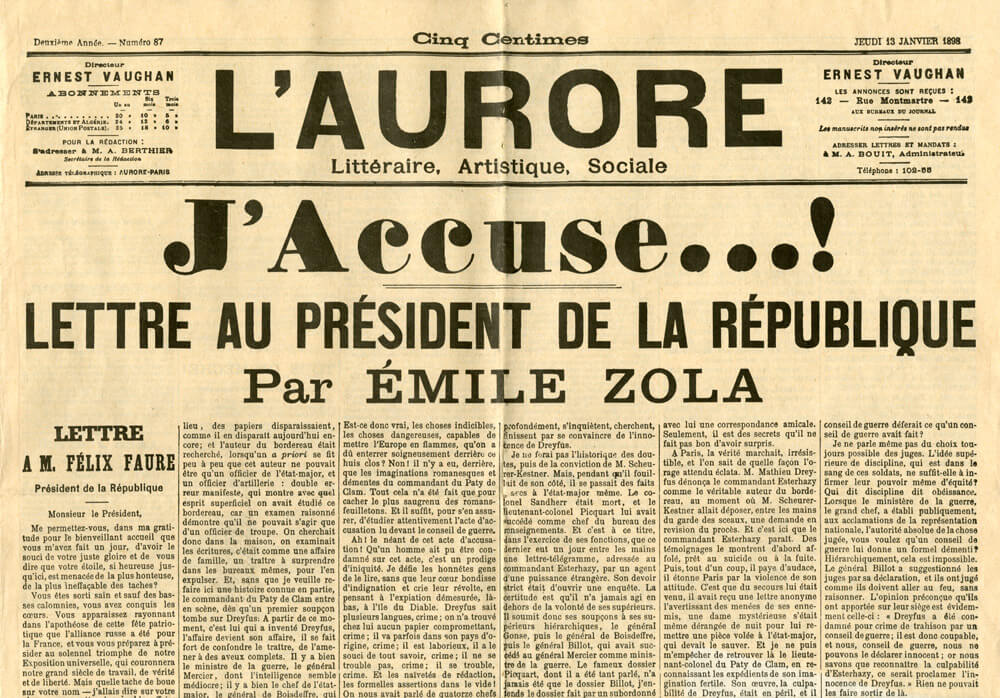

The Dreyfus affair

Clemenceau is a central player from 1897 onwards in the rehabilitation of Captain Dreyfus, who had been unjustly convicted by a military tribunal for spying. Alongside Jean Jaurès and other writers and intellectuals, he fights tirelessly to overturn the judgement. In January 1898, he gives the famous title of J’accuse to Emile Zola’s decisive l’Aurore diatribe against the Army General Staff. Clemenceau would produce no less than 665 articles in various publications until truth and justice prevails. In 1908 and just a few years after Zola’s death, Clemenceau as head of the government arranges for Zola’s ashes to be moved to the Pantheon.

Minister of the Interior (14 March 1906–20 July 1909) – President of the Council (25 October 1906–20 July 1909)

A senator from Var since 1902, Clemenceau is named Minister of the Interior on 13 March 1906. This is his first ministerial title at 65 years of age and he retains the position when he becomes President of the Council just a few months later. The Clemenceau government passes important social legislation covering workers’ pensions, the ten-hour workday and unions. Clemenceau appoints René Viviani as the first Minister of Labor and moderates aspects of the church property inventories required by the 1905 law on the Separation of Church and State. He avoids getting entangled in Moroccan colonialization and favors diplomatic rapprochement with Japan in Asia.

In a bid to modernize the police, he picks Célestin Hennion to head the Surêté Générale police division. Hennion creates specialized regional crime fighting units known as the mobile brigades, implements the latest scientific techniques, introduces automobiles to the police force and equips police officers with a more effective handgun. Clemenceau faces strikes in the north following the Courrières mine disaster and in the southern wine regions.

After attempting negotiations with the strikers and anxious to prevent disorder, Clemenceau repeatedly calls in the troops to control the situation. This alienates the Socialist left led by Jean Jaurès and the verbal battles in parliament between Clemenceau and Jaurès become famous.

Father of Victory

In the initial years of the Great War, Clemenceau plays an active role as chairman of the Senate’s Foreign Affairs and Armed Services Committees. His criticism of the civil and military authorities, though, flouts the censors: Clemenceau’s newspaper, L’Homme Libre (The Free man), suspends publication in September 1914 before reappearing as L’Homme Enchaîné (The Chained Man). In November 1917, at the height of France’s national distress, President Raymond Poincaré calls on Clemenceau to form the government. Serving both as President of the Council and Minister of War until his withdrawal in early 1920, Clemenceau exhibits an iron will and undisputed authority. He imposes the union of allied forces under the sole command of Ferdinand Foch, announces the armistice in the National Assembly on 11 November 1918 and is the main French architect of the Treaty of Versailles negotiated with British Prime Minister Lloyd George and the American President Woodrow Wilson. Clemenceau would later write about this period in his posthumous work, Grandeur and Misery of Victory.

MAN OF LETTERS – FRIEND TO ARTISTS

Famous for his political career, Georges Clemenceau is less well known for his writings. Literature, though, is no mere hobby for him. Clemenceau is an exceptional letter writer and throughout his life publishes articles, short stories, essays, as well as a novel, play and biography. He tackles all genres with the exception of poetry and aspires to be a man of letters. Like many authors of his day, he starts in the press. In 1895, he gathers a selection of his articles in his first published work, La Mêlée sociale. Other political and literary titles would follow including two works of fiction: a 1901 novel, The Strongest, and a « Chinese » play, The Veil of Happiness, which has been staged a number of times. His retirement is prolific. Alongside a vast political and philosophical testament, In the Evening of my Thought, and a book defending and illustrating the work of Claude Monet, he offers his last love, Marguerite Baldensperger, a Demosthenes, where he implicitly plays the role of the Greek orator.

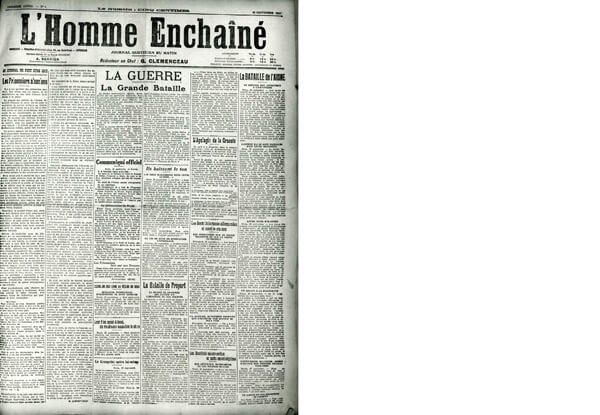

Clemenceau the journalist

Clemenceau’s forced retirement from parliament after the 1893 Panama scandal leads him to become a full-time journalist at 52 years old. Until his election to the senate in 1902, he lives off his writing and publishes thousands of articles, ten per week in la Justice, l’Aurore, la Dépêche du Midi and various other press outlets. His articles on the Dreyfus Affair, essential to the combat for the innocent officer’s defense, fill six volumes. Between January 1901 and March 1902, he is sole editor of a weekly journal he names le Bloc. Later he is a constant presence at l’Homme libre (The Free man), a newspaper he founds and then renames l’Homme enchaîné (The Chained man) after being censored during WWI. His pen only rests during his periods in the government.

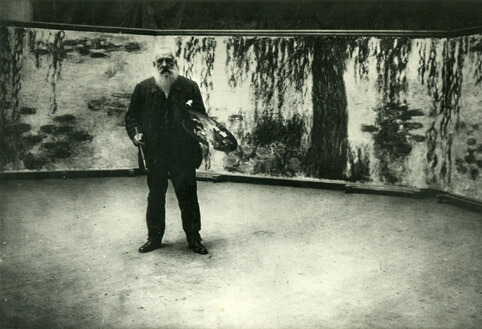

Clemenceau and the artists

Clemenceau is passionate about art throughout his life. Introduced to contemporary art by his friend Gustave Geffroy, Clemenceau is a critic, patron and defender of the great artists of his day, such as Manet or Whistler, whose best works are acquired by the national museums under his impetus. In the 1880s, a fondness for Japanese art drives him to collect prints and incense boxes.

Late in life, his longstanding friendship deepens with Claude Monet. Clemenceau is an untiring supporter and encourages Monet’s Water Lilies donation and installation at the l’Orangerie museum.

« When the water garden lilies transport us from the liquid plain to the travelling clouds of infinite space, we leave the earth and its sky to experience fully the supreme harmony of things ».

Clemenceau is painted by Manet, Raffaëlli and Eugène Carrière and his bust is modeled among others by Rodin. Gustave Geffroy writes that Rodin’s work captures « in an admirable and definitive bronze all the energy and force of the indomitable man ».